We have been reaching out to our network of creative placemaking experts, deep thinkers, and professional creative people to contribute juicy reads on issues that rub up against our world of art and culture.

This week friend and collaborator Carolina Tötterman explores creative clusters, and the long-lasting legacy of one the most well-known creative cluster effects: the Chelsea Hotel, in New York City.

Anyone participating in the development of spaces and places and meaningful engagements within the communities they build into might be interested in the principles and phenomenon of creative clusters, and their benefits.

Creative clusters are basically a scene made up of primary makers/creators along with small, specialised secondary and tertiary enterprises that support them (often highly individualised businesses in their own right). Clusters and scenes set the character and tone of a place.

Poets, authors, painters, photographers, playwrights, sculptors, jewellery-makers, costume designers, filmmakers, et al are historically sensitive to rising rents and need specialised spaces to work in. Preserving and encouraging inner city creative scenes where these people can work ensures that our urban centres feature something more than cashed up, high-tech startups, digital agencies and sleek architecture firms.

The consequence of erasing urban makers and creators from ‘the mix’ is erosion of creative clusters which then leads to, decimation—if not annihilation—of the original vibe, attitude and character that made a place so interesting and appealing to begin with.

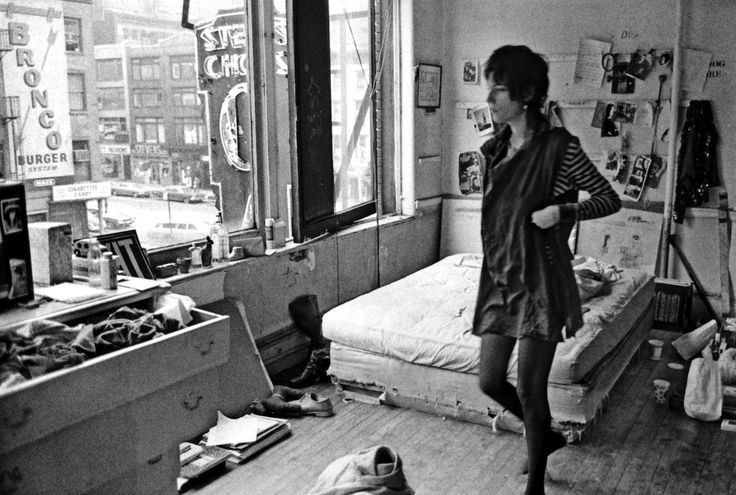

The famed twelve-storey Chelsea Hotel, opened in 1884, within cooee of New York City’s then bohemian Greenwich Village and theatre district, is a prime example of a developer purposefully ensuring creative practitioners had a place to work, connect and rub shoulders with others in. Writers, artists, filmmakers, rockers, composers, poets, actors, dancers, designers, choreographers, curators, critics—creators of all kinds—produced an abundance of iconic works behind those three-feet deep, red brick walls. The Chelsea is now recognised as a city landmark and a crucible for creativity.

What the Chelsea’s story gives us is not only a roadmap on how to preserve urban communal spaces for creative practitioners, but also insight into the cultural benefits of cultivating and encouraging creative clusters and scenes.

Originally built as the jewel-in-the-crown of a suite of private co-operative buildings built by French-American Philip G Hubert, The Chelsea was a manifestation of a French dream. A child of Paris during its socialist revolution and devotee of the theories of the utopian, Hubert was a believer in Fourier’s vision of a society where workers, scholars and artists lived and worked side-by-side in four-storey buildings. named ‘Phalanstères’. Fourier was convinced his vision would lead to inventions ‘proliferating’ and the production of a ‘Milton or Molière’ with every generation’.

Fast forward to New York City in the 1880s, where Hubert was now living, working and putting his ‘Fourieran’ ideals into practice. He made a name and money for himself through his co-operative ‘apartment houses’ known as ‘Hubert Home Clubs’ and set out to fulfil an ambitious plan to construct a residential co-op on a scale Fourier could only ever have dreamed of; The Chelsea Association Building.

Hubert’s dream was for a creative, communal mass-residence catering to those with a taste for, ‘novelty, social interaction, intellectual stimulation and creative work’ in the ‘most tolerant and cosmopolitan’ part of New York City. And before the doors had even opened a number of up-and-coming painters had signed up as members or tenants, along with families of music and arts students attending the nearby drama and music schools, producers, impresarios and actors from the adjacent theatre district.

“Hubert carefully designed communal spaces, such as the lobby with a grand fireplace and Hudson River School paintings hanging on the walls, multiple rooftop gardens, linked dining rooms, a frescoed sitting room, billiards parlour, eight-foot-wide corridors (so residents could meet, talk and linger), shared kitchens and a light-filled staircase that connected it all.”

While initially successful, the bloom of both the co-op movement and The Chelsea faded and it changed hands to re-open as a luxury hotel in 1905. The Chelsea vibe however still drew in creators like Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, John Sloan the painter and vibrant theatre and opera people. Bankruptcy in 1939 saw The Chelsea change hands again, this time to a trio of European immigrants with David Bard at the helm. Bard was sympathetic to the The Chelsea’s creative legacy and supported it.

After World War II, room prices fell and the likes of Jackson Pollock, Virgil Thomson, Larry Rivers and Dylan Thomas moved in. When David Bard died in 1957 his son Stanley took over as majority owner and manager, continuing in the role for a further 50 years.

With Stanley Bard the scene was set for a prolonged blossoming of creativity that would be home to some of the most iconic creators of the late 20th century. But why?

“Stanley Bard inherited a building with a creative provenance unlike any other in New York, however he also proved to be an expert cultivator who would encourage the artistic ambitions of the hotel’s residents while balancing an eclectic flow of transients and overnighters to keep it all ticking over.”

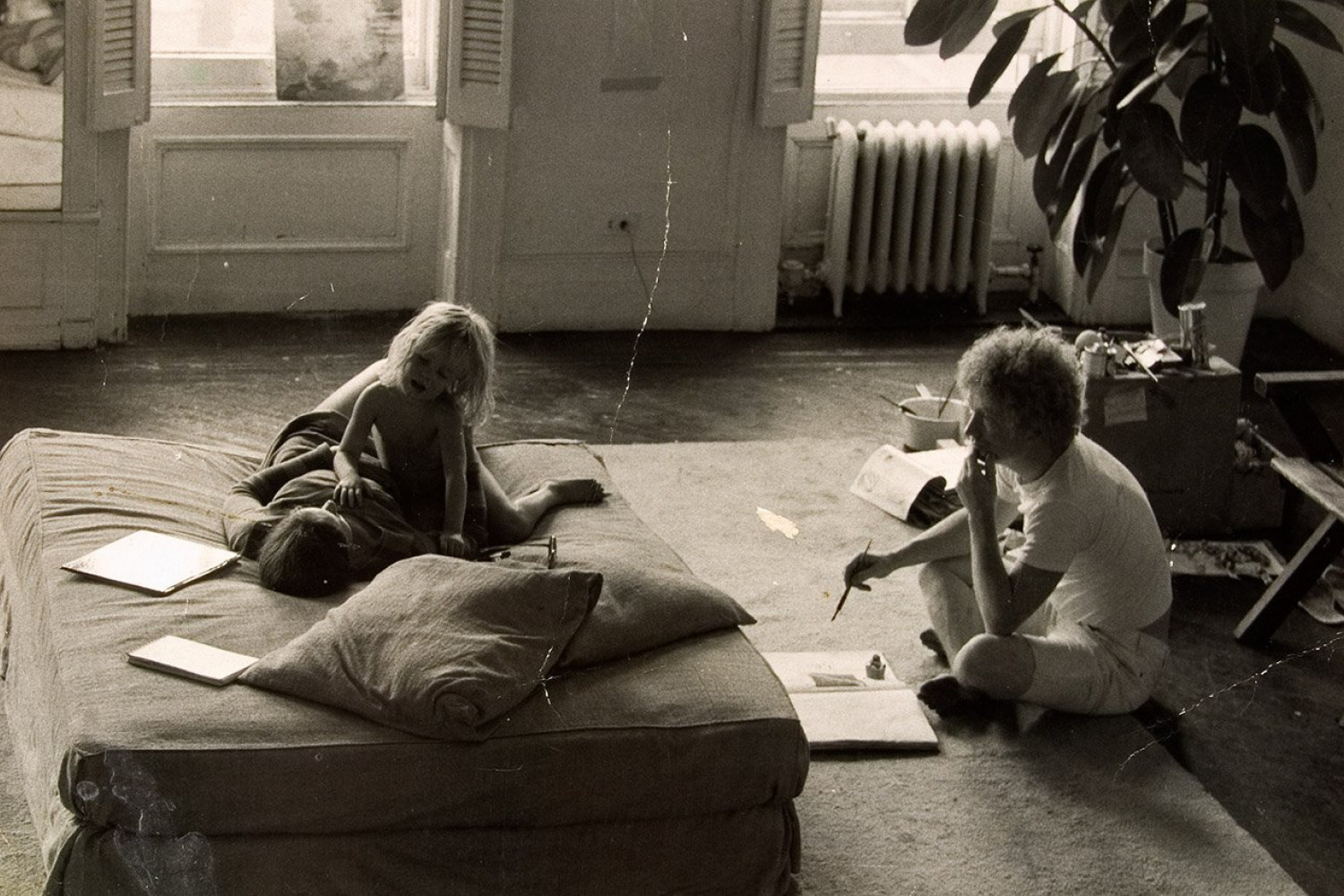

Composer Gerald Busby described Stanley in a Vanity Fair article as someone who, “had a sense of who was really an artist”. It was Stanley’s efforts that provided the loam for creative output that is so substantial and illustrious it wildly surpassed Charles Fourier’s 19th century vision of a ‘Milton or Molière’ once every generation. Visitors and residents alike would comment on the vibe during the Stanley era and long-time resident and author Ed Hamilton, described it as electric, ‘like a charge running through the hotel that hit you as soon as you stepped into the lobby and [a] wide-open sense of possibility.’

The framework Phillip G Hubert set in place for interactions and serendipitous cross-fertilisation—originally 15 dedicated artist studios on the top floor and 80 apartments (50 for members and 30 for rentals to keep a flow of people and funds circulating)—was based on the idea of the wealthier, bigger tennants subsidising, in a sense, the artisans in the rooftop studios and smaller apartments who, in return, injected creative energy into the Chelsea biosphere.

The purposefully carved out common areas were part of what gave The Chelsea its ‘affect’ as playwright Arthur Miller described; “it was thrilling to know that Virgil Thomson was writing his nasty music reviews on the top floor, and that those canvases hanging over the lobby were by Larry Rivers […] and that the hollow-cheeked girl on the elevator was Viva and the hollow-eyed man with her was Warhol.”

“The Chelsea playbook is a model contemporary businesses, planners and savvy developers can consult to mitigate the displacement of artists and arts organisations that can be triggered by urban developments, and not just as short-term stints while DAs and plans are pending.”

As the story of The Chelsea and the unprecedented amount of creativity it was a hot house to shows, the power of cultivating and keeping creators and makers in the communities they seeded and helped shape is a practical way to encourage civic engagements and vibrancy for the benefit of all.

Carolina Tötterman is the founder and editor of cultivator.network, a social enterprise that fosters knowledge exchange between creative practitioners. She has been operating in the creative industries in Sydney as a creative producer/content creator, arts marketer and educator for two decades.

*A collection of just some of the makers and creators who lived and worked at The Chelsea.

Mark Twain, Tennessee Williams, Allen Ginsberg, Arthur Miller, Brendan Behan, Edgar Lee Masters, Gore Vidal, Dylan Thomas, Jack Kerouac, Simone de Beauvoir, Robert Oppenheimer, Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Wolfe, Stanley Kubrick, Dennis Hopper, Eddie Izzard, Elliott Gould, Jane Fonda, Sarah Bernhardt, The Grateful Dead, Chet Baker, Tom Waits, Patti Smith, Virgil Thomson, Bob Dylan, Alice Cooper, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Canned Heat, Dee Dee Ramone, Iggy Pop, Madonna, Rufus Wainwright, Madonna, Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Keith Richards, Sid Vicious, Leonard Cohen, Arthur B Davies, Larry Rivers, Willem de Kooning Yves Klein, Brett Whiteley, Sidney Nolan, Christo & Jean Claude, Francisco Clemente, Robert Mapplethorpe, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Robert Crumb, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Mark Rothko, William De Kooning, Henri Cartier- Bresson, Jean Tinguely, Julian Schnabel, Susanne Bartsch, Charles James, Betsey Johnson*